Korean Fermented Foods Beyond Kimchi Doenjang Gochujang

Discover the deep flavors of Cheonggukjang, Jeotgal, and Jangajji. A comprehensive guide to Korea's lesser-known fermented treasures for foodies.

When international travelers think of Korean cuisine, the "Holy Trinity" of fermentation—Kimchi, Doenjang (soybean paste), and Gochujang (red chili paste)—dominates the conversation. While these three pillars are fundamental, they represent only a fraction of Korea's fermentation universe, known locally as balhyo. In 2025, culinary surveys indicated that while 98% of tourists try kimchi, fewer than 15% venture into the deeper, more pungent, and often more medicinal world of Korea's other fermented specialties.

For the true gastronome, the magic lies in the lesser-known jars. From the rapid-fire fermentation of Cheonggukjang to the saline complexity of Jeotgal, these foods offer a masterclass in preservation and flavor depth. This guide explores the savory, salty, and sometimes challenging flavors that define the true Korean palate, providing you with the knowledge to order like a local and appreciate the science behind the smell.

You might also enjoy our article about Korean fermented foods beyond Kimchi cheonggukjang and meju.

Key Takeaways

- 1Cheonggukjang is a quick-fermented soybean paste offering 100x more probiotics than typical yogurt.

- 2Jeotgal (salted seafood) ranges from budget-friendly squid at ₩5,000 to premium roe costing ₩50,000+.

- 3Jangajji pickles use soy sauce or vinegar to preserve vegetables for up to 3 years.

Cheonggukjang: The Potent Powerhouse

If Doenjang is the slow-aged wisdom of the Korean kitchen, Cheonggukjang is its energetic, impulsive cousin. Unlike Doenjang, which ferments for months or years, Cheonggukjang is a quick-fermented soybean paste, typically ready to eat in just 2 to 3 days.

You might also enjoy our article about Korean Soup Culture Guide 2026 Kimchi Jjigae Doenjang Jjigae.

The result is a texture that remains largely whole—you can see and chew the individual soybeans—and a smell that is undeniably potent. Often compared to pungent French cheeses or Japanese Natto, Cheonggukjang contains a specific bacterium, Bacillus subtilis, which creates a sticky, stringy mucilage responsible for its distinctive texture and health benefits.

For more details, check out our guide on 50 Must Try Korean Foods Complete Guide.

📋 Cheonggukjang Profile

The Health Paradox

Despite its strong odor, Cheonggukjang is widely considered one of the healthiest foods in the Korean diet. A 2024 study by the Korea Food Research Institute highlighted that a single serving (approx. 200g) of Cheonggukjang stew contains significantly higher levels of polyglutamic acid—a powerful immune booster—compared to long-fermented pastes. It is particularly revered for its thrombolytic enzymes, which help dissolve blood clots.

Related reading: Best dessert cafes in Seoul 2026 beyond Bingsu.

Pro Tip

If you are sensitive to strong smells but want the health benefits, look for "Odorless Cheonggukjang" (Naemse-eomneun Cheonggukjang) in supermarkets. It retains 90% of the nutrients with only 20% of the pungency.

Where to Try It

While you can find it in supermarkets, the best Cheonggukjang is found in specialized restaurants in older districts or rural areas.

Sigol Bapsang(Sigol Bapsang)

Jeotgal: The Ocean Preserved

Jeotgal refers to salted, fermented seafood. While often used as a hidden seasoning in kimchi (providing that essential umami kick), Jeotgal is also enjoyed as a standalone side dish. With over 160 documented varieties in Korea, this category is vast. The fermentation process relies on a high salt concentration—typically 20% to 30% by weight—which inhibits bad bacteria while allowing enzymes to break down the proteins into amino acids.

Popular Varieties for Beginners

- Ojing-eo-jeot (Squid): Chewy, sweet, and spicy. This is the "gateway" Jeotgal for foreigners. It is usually seasoned with chili powder, garlic, and corn syrup.

- Myeongnan-jeot (Pollack Roe): The caviar of Korea. Rich, creamy, and savory. It originates from Korea (historically recorded in 1652) and was later popularized in Japan as Mentaiko.

- Nakji-jeot (Octopus): Similar to squid but with the distinct texture of octopus suction cups.

💵 Jeotgal Market Prices (Per 500g Jar)

Low-salt, whole roe sacks, artisanal.

Sweet and spicy, widely available.

The Culinary Usage

In contemporary Seoul dining, chefs are elevating Jeotgal beyond a simple side dish. You will now find Myeongnan pasta in Gangnam cafes priced around ₩18,000 to ₩24,000, or Saeu-jeot (salted shrimp) used to season premium pork belly at BBQ restaurants.

"When buying Jeotgal at a traditional market like Sorae Pogu, always ask for a taste ('Mat-boseyo?'). The vivid red color should come from quality chili, not artificial dye. Good Jeotgal should smell like the ocean, not fishy rot."

Jangajji: The Art of Vegetable Pickling

While Kimchi involves fermentation that produces acid and gas (active culture), Jangajji is preservation through submersion in soy sauce, soybean paste, or vinegar brine. These non-fermenting or slow-fermenting pickles were historically crucial for preserving seasonal vegetables for the harsh Korean winters.

Today, they act as the perfect palate cleanser. The salt content in traditional Jangajji can be high, often exceeding 10%, but modern variations served in restaurants usually sit closer to 4-5% to accommodate lighter tastes.

Top 3 Jangajji to Try

- Myeongina-mul (Pickled Garlic Leaves): The ultimate companion to Korean BBQ. It grows wild on Ulleungdo Island and costs roughly 30% more than other pickles due to its scarcity.

- Maneul-jong (Garlic Scapes): Crunchy, sweet, and garlicky stems.

- Gochu-jangajji (Pickled Green Peppers): Often soaked in soy sauce, these provide a spicy, salty burst.

📖 How to Eat Myeongina-mul at a BBQ

Step 1: Select the Leaf

Take one single leaf of Myeongina-mul from the side dish plate. It is sticky, so peel carefully.

Step 2: Place the Meat

Place your grilled pork belly (Samgyeopsal) in the center of the leaf.

Step 3: Wrap and Eat

Roll the leaf around the meat. Do not add extra salt or dipping sauce; the leaf is seasoned enough.

Makgeolli: The Fermented Rice Elixir

No discussion of Korean fermentation is complete without the liquid courage that accompanies it. Makgeolli is Korea's oldest liquor, a cloudy, lightly sparkling rice wine typically boasting 6% to 9% alcohol by volume.

Unlike Soju, which is distilled, Makgeolli is brewed using Nuruk—a fermentation starter cake made of wheat, rice, and water containing wild yeasts, molds, and bacteria. This complex microbial ecosystem gives Makgeolli its signature flavor profile: sweet, sour, bitter, and astringent.

The Makgeolli Renaissance

Ten years ago, a bottle of Makgeolli in a convenience store cost ₩1,200 ($0.90 USD). While those budget options still exist, the market has exploded with premium artisanal brews. Craft Makgeolli bars in neighborhoods like Hongdae and Seongsu now serve bottles aged for 30 to 90 days, with prices ranging from ₩15,000 to over ₩80,000 ($11 - $60 USD).

📊 Makgeolli Market Trends

Fresh (Saeng) Makgeolli vs. Pasteurized

- ✓Contains live active cultures (probiotics)

- ✓Ever-changing flavor profile

- ✓Natural carbonation

- ✗Short shelf life (10-30 days)

- ✗Must be kept refrigerated

- ✗Risk of leaking during travel

Cheong: The Enzyme Syrups

If you visit a Korean home, you might see large glass jars filled with fruit and sugar sitting in a cool corner. This is Cheong, or enzyme syrup. By mixing fruit (like green plums, citron, or berries) with an equal weight of sugar, the osmotic pressure draws out the juice, which then ferments slowly over 3 to 12 months.

The most famous is Maesil-cheong (Green Plum Syrup). It is a household essential, used as a sugar substitute in cooking and as a digestive medicine. If you have an upset stomach after too much spicy food, a cup of warm water mixed with 30ml of Maesil-cheong is the local remedy.

Common Korean Syrups (Cheong)

| Type | Main Ingredient | Primary Use | Best Season |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maesil-cheong | Green Plum | Digestive Tea / Marinades | June |

| Yuja-cheong | Citron (Yuzu) | Hot Tea for Colds | November |

| Omija-cheong | Five-flavor Berry | Summer Iced Drink | September |

Bringing Flavors Home: Logistics and Regulations

For travelers wishing to bring these fermented goods back to their home countries, careful planning is required. Fermented foods are "alive," meaning they can produce gas and expand during flight.

Packing Guidelines

- Vacuum Seal: Always ask the vendor for "Vacuum po-jang" (vacuum packing). Most traditional markets charge ₩1,000 to ₩2,000 for this service.

- Hard Containers: For Jeotgal or soybean pastes, transfer vacuum-sealed bags into hard plastic Tupperware to prevent crushing.

- Check-in Luggage: Pastes and liquids (including moist kimchi and jeotgal) exceeding 100ml are strictly prohibited in carry-on bags at Incheon International Airport. You must check them in.

Explosion Warning

Do not bring "Fresh" (Saeng) Makgeolli in your luggage. The active yeast continues to produce CO2. The pressure changes in the cargo hold will almost certainly cause the bottle to explode, ruining your suitcase. Only buy pasteurized (sterilized) Makgeolli for air travel.

Shopping Journey: Gwangjang Market

Arrive

Enter via North Gate 2 for the savory food section.

Tasting

Visit the Jeotgal aisle (Section 45-50). Try 3 varieties.

Purchase & Pack

Buy 500g jars. Request heavy-duty wrapping for flights.

Conclusion

Korea's fermentation culture is a testament to the nation's history of resilience and connection to nature. Beyond the ubiquitous kimchi, the intense aroma of Cheonggukjang, the briny depth of Jeotgal, the crisp bite of Jangajji, and the sweet haze of Makgeolli offer a fuller picture of Korean gastronomy.

Venturing into these flavors requires a sense of adventure. The smells may be strong, and the textures unfamiliar, but they reward the palate with complexity found nowhere else on earth. So, on your next trip to Seoul, look past the red chili paste and ask for the fermented treasures hidden in the back of the pantry.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Have more questions?Contact us →

About the Author

Korea Experience Team

Written by the Korea Experience editorial team - experts in Korean medical tourism, travel, and culture with years of research and firsthand experience.

Explore more in Food & Dining

Korean BBQ, street food, Michelin restaurants, and regional specialties — your ultimate guide to eating well in Korea.

Browse All Food & Dining ArticlesContinue Reading

Explore more articles you might find interesting

Master Korean food delivery apps in 2026. From Coupang Eats to Baemin, learn how to order like a local with our complete English guide.

Discover the deep flavors of Korean fermented foods beyond kimchi. A comprehensive 2026 guide to Cheonggukjang and Meju for adventurous travelers.

A comprehensive guide to buying Korean ginseng and energy tonics in 2026.

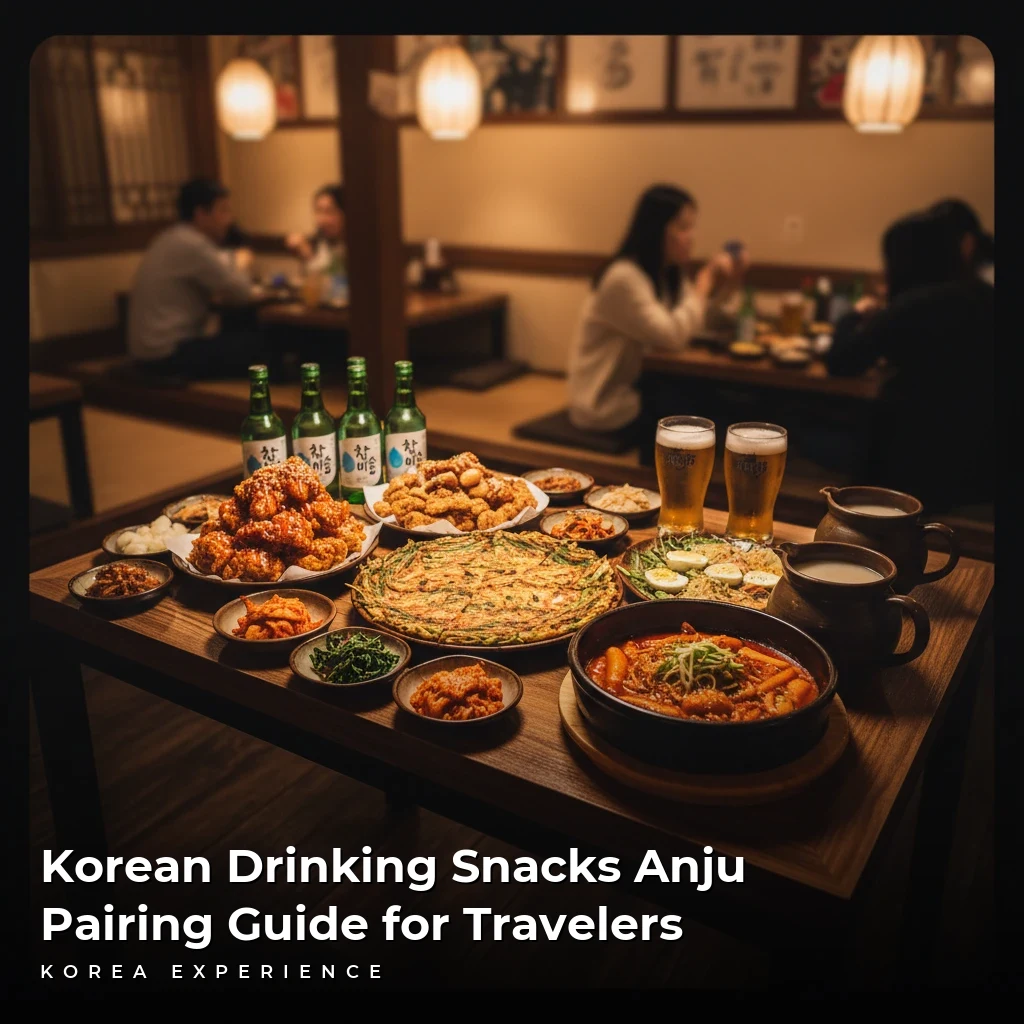

Master the art of Korean Anju pairings with our expert guide to Soju, Makgeolli, and Beer snacks for the ultimate local dining experience

Master the art of recovery in Seoul. From savory Haejangguk soups to convenience store elixirs, here is your essential guide to Korean hangover cures.

The ultimate guide to Korean drinking games rules, etiquette, and culture. Learn how to play Titanic, Soju Cap, and more like a local expert.